The media prophets report no future for capacity building of Community Media

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Date: June 13, 2011

Contact: Belinda Rawlins, (617) 287-7371, belinda@transmissionproject.org

BOSTON – The FCC’s “The Information Needs of Communities,” released last Thursday, represents a departure from previous reports in that it more fully recognizes community media outlets as key providers of digital and media literacy. However, the report misses the opportunity to make specific recommendations for strengthening and expanding these organizations’ ability to meet the needs of communities:

We applaud the community media centers that have moved to become key venues to help train citizens in digital literacy. We recommend that community media centers explore ways to help increase digital literacy and broadband adoption, and that policymakers consider community media centers as a resource that can aid in efforts in those areas. (357)

The Transmission Project has ten years of experience building the capacity of community media organizations that deliver digital and media literacy. A national service initiative, our Digital Arts Service Corps places volunteers with organizations to complete yearlong capacity building projects. In fact, many of the report’s examples of strong community media organizations have benefited from our Digital Arts Service Corps. The report mentions CAN TV in Chicago, Cambridge Community Television, Boston Neighborhood Network, Media Bridges Cincinnati, and Saint Paul Neighborhood Network (SPNN), whose Community Technology Empowerment Project emerged out of a collaboration with the Transmission Project.

In the past, the FCC has explicitly acknowledged the value of service-based models in promoting digital literacy. It is therefore disappointing that missing from the report is any recommendation regarding what role service and volunteerism should play in meeting the digital literacy needs of communities. Recommendation 9.3 of the FCC’s National Broadband Plan provided a framework for the creation of a National Digital Literacy Corps under the NTIA that would possibly entail a collaboration with the Corporation for National and Community Service. The Plan also recommended capacity building of digital literacy partners under IMLS. As neither of these recommendations has come to fruition, the newly released report served as an opportunity to elaborate on or explore alternatives to the previously proposed partnerships.

The FCC’s “The Information Needs of Communities” alludes only once to volunteer corps when it criticizes the possibility of AmeriCorps volunteers serving as journalists. Indeed, Transmission Project Executive Director Belinda Rawlins provided the FCC report’s working group with comment to the same effect. The report echoes her words:

There is one public-private partnership we think would be a bad idea: some have suggested creating a federally-funded AmeriCorps program for journalists. Journalism should often be about challenging powerful institutions, which sometimes will draw political fire and controversy. AmeriCorps has grown and prospered by focusing on the forms of service on which most Americans can agree, such as tutoring, helping seniors, or working for Habitat for Humanity. Creating a government-financed AmeriCorps for reporters would potentially seriously harm AmeriCorps. (357)

Although the report correctly defines the limits of AmeriCorps involvement, it declines to discuss how other corps models can help. Paid volunteers should not be barred from building the capacity of community media organizations. The Transmission Project is pained to see that the report’s working group seems unable to imagine a role for national service in helping to build a robust, diverse media infrastructure beyond directly serving journalistic enterprises.

We are still taking in the sizable report, and in the coming weeks we plan to explore in more depth various digital and media literacy curricula. In the meantime, we hope readers will refer to the Transmission Project’s previous statements on service corps models and digital literacy.

“Google Announces Launch of Technology Corps”

“In Pursuit of New Literacies”

The Transmission Project amplifies the power of public media and technology. The Transmission Project supports a diverse network of partner organizations that serve communities nationwide. Through our primary initiative the Digital Arts Service Corps, we recruit and place full-time AmeriCorps*VISTAs (Volunteers in Service to America) with organizations to complete specific, yearlong capacity building projects.

Show me your publics, and I’ll show you mine

Reading the title chapter of Michael Warner’s 2002 collection of essays Publics and Counterpublics, I am struck by how the book resonates with my work with the Transmission Project. It has helped me think through and beyond the rhetoric I encounter every day.

Professionals in the field speak endlessly of “community-engagement,” “community feedback,” and/or “community opinion.” Recently these terms have been popping up in my research of online vote-for-me contests and in online forums that claim to capture “community opinion” by allowing users to comment on various topics or ideas for change. How these sites describe community action coincides with Warner’s explanation of the normative ways we ascribe agency to a public, an otherwise abstract space for the circulation of ideas:

All of the verbs for public agency are verbs for private reading, transposed upward to the aggregate of readers. Readers may scrutinize, ask, reject, opine, decide, judge, and so on. Publics can do exactly these things. And nothing else. Publics – unlike mobs or crowds – are incapable of any activity that cannot be expressed through such a verb. Activities of reading that do not fit the ideology of reading as silent, private, replicable decoding – curling up, mumbling, fantasizing, gesticulating, ventriloquizing, writing marginalia, and so on – also find no counterparts in public agency” (123).

Community participation as imagined in many online spaces resembles Warner’s understanding of publics as essentially readerly – able to act only in ways one would act in relation to a text. Innovative as such online tools are, they still render community agency as an interpretive and analytical function and not as specifically collective practice or group action. The Transmission Project has argued on behalf of more expansive definitions of public and media that include as broad as possible a range of approaches of group participation and communication. An open-ended definition is central to the Project’s understanding of how media can transform people’s lived experience.

In a similar attempt to make room for new imaginings of public life, Warner offers the notion of a counterpublic, which he defines as, “a scene where a dominated group aspires to re-create itself as a public and in doing so finds itself in conflict not only with the dominant social group but with the norms that constitute the dominant culture as a public” (112). Organizations hosting Digital Arts Service Corps members serve people of color, immigrant groups, women, and youth, all of whom could be described as being subject to oppression. However, members’ pre-existing identities or their oppositional stance toward power do not define them as a counterpublic. (More important is how participation in a public shapes or transforms identity.) Rather, Warner suggests, counterpublics are “counter” to the extent that they offer alternative ways of participating in public life. His example of 18th century She-Romps are characterized not by their female membership, but by how these clubs of rowdy women rejected conventions of public politeness and modesty. Counterpublics imagine their terms of membership differently from conventional notions of participation in public life.

Taken from the Center for Social Media, one of my favorite quotations that the Transmission Project has used and reused effectively imagines publics as emerging by way of something other than the act of readerly discourse:

People come in as participants in a media project and leave recognizing themselves as members of a public — a group of people commonly affected by an issue. They have found each other and exchanged information on an issue in which they all see themselves as having a stake.

Creating media plays a generative role here beyond conveying the opinions of the creators. The way I read this statement, the newly-formed public does not preexist its members’ participation in an act of co-creation. Rather, participation in creation serves as the condition of membership for the new public. Similarly, the participants’ common stake in an issue did not previously define them as individuals. Membership has transformed their identities. In this example, collective creation of media supersedes private reading as the action that defines the public as such. In this regard, it borrows from models of popular education in which instruction is not delivered down to students who then produce individual responses. Instead, learners share lessons with each other. Because it offers a non-normative vision of participation in public life, the excerpt serves for me as an allegory of transformative public media.

To what extent do the community media projects your organization runs coincide with Warner’s concept of counterpublics? As community media movements build steam, I hope we continue to think critically about how we imagine participation and forge new forms of engaging in public life. Until then, let the She-Romps romp!

Google Announces Launch of Technology Corps

Yesterday Google announced in a blog post that it is launching the HandsOn Tech Corps in collaboration with HandsOn Network, the volunteer arm of Points of Light Institute. Starting this September, the new volunteer corps will develop “technology capacity” that “will help organizations to address mission critical activities more effectively and efficiently.” The Transmission Project congratulates Google on launching an initiative that addresses the demands for capacity building of community-based nonprofits and for the establishment of a national digital literacy corps as laid out in the National Broadband Plan and other policy papers.

Many facets of the HandsOn Tech Corps resemble the Transmission Project’s Digital Arts Service Corps, and Google’s intentions reflect the values of the Transmission Project – in principle if not in practice. Like the Digital Arts Service Corps, HandsOn places AmeriCorps*VISTA members with nonprofits to complete a yearlong capacity building project. Comparable to the Transmission Projects support network, the new corps provides its paid volunteers with guidance and training beyond what AmeriCorps members would receive working independently in the field. Says Google, the Tech Corps will begin

with a one-week training at our campus in Mountain View, learning about both our nonprofit tools and cloud-based offerings from other technology companies like Salesforce.com and LinkedIn. Once they are armed with tech know-how, they’ll spend the rest of the year in three-person teams serving nonprofits in the Bay Area, Atlanta, Chicago, Detroit, New York City, Pittsburgh and Seattle.

In the Tech Corps model, the Transmission Project recognizes its own conviction that technology has a role to play in AmeriCorps*VISTA’s mission of strengthening “nonprofits that are working to lift people out of poverty.”

Google’s commitment is certainly a step in the right direction. However, we wish Google and HandsOn would place the particular needs of organizations at the forefront of their new initiative. Google mentions that its Tech Corps members will be trained in its own nonprofit tools. Although familiarity with these tools may prove helpful to some, the solutions its Corps will be able to offer organizations after this kind of training are still highly prescriptive and techno-centric. Nonprofits need and deserve to have a voice in determining the nature of the project that will presumably transform their organizations. For Corps members, much more important than technology skills are the skills to collaborate with organization staff and work toward a solution. For organizations, a technology solution that is well planned-for and has the support of staff is more valuable than a predetermined set of technology practices. Rather than prescribing specific practices, the Transmission Project has served as adviser during the project design process, so that organizations are prepared to maximize the impact that the addition of a Digital Arts Service Corps member makes.

If Google wants to honor its commitment to building the capacity of grassroots nonprofits through technology, it will take into account the work of those already doing so. And it better do so soon. As the Transmission Project departs, it leaves behind a wealth of knowledge and experience. This includes a respect for diverse, grassroots media arts organizations. We invite anyone desiring to take from our ten year history to use the Transmission Project’s legacy in their work.

Feedback Process Inspires Surge of Support

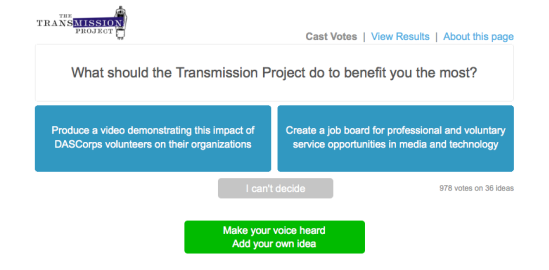

Two weeks ago the Transmission Project began soliciting feedback from its allies and partner organizations regarding what specific projects we can do over the next few months to help assure our legacy remains relevant to your work in the future. We were impressed by the effort you put forth.

To facilitate the idea-vetting process, we experimented with the All Our Ideas tool, which presented feedback-contributors with two project ideas at a time and asked them to choose the one they would most like to see put into action.

Our petition for your feedback yielded a tremendous amount of participation. During the feedback period from May 2 to May 11, we received 978 votes from approximately 237 friends and supporters. In addition to voting on the 30 ideas that Transmission Project staff suggested, participants proposed their own ideas. We received 6 additional project ideas from our allies, some of which made it to the top of the list.

Using participants’ feedback, the tool calculates a particular project idea’s chance of being chosen over another, randomly selected idea. Here are the top five ideas:

Transmission Project thanks you for your support in giving us your input. We are still analyzing results and taking our capacity into account as we move forward on some of these ideas.

We will say, however, that we were saddened to see that some of the “less conventional” ideas did not make it very far. As per your preference, the Transmission Project will not be engineering a branding iron in the shape of its logo.

For more ways to have a hand in the Transmission Project’s future, visit the Legacy Page.

Digital Arts Service Corps at NCMR

Members, alumni, and supervisors of the Transmission Project’s Digital Arts Service Corps will be putting in appearances as presenters over the course of this weekend at the National Conference for Media Reform in Boston. Below we’ve provided their names, their relationships to the Corps, and the sessions where you can find them this weekend.

Gavin Dahl, currently serves at Common Frequency, “Put Your Hands on the Radio”

Anne Jonas, currently serves at Participatory Culture Foundation, “Open Sourcing Community media, Cutting the Cord: the Future of Video”

Nicole Belanger, served at the Sanctuary for Independent Media, now Community Media & Technology Coordinator at Cambridge Community Television, “Creating and Sustaining Citizen Journalism”

Brandy Doyle, served at the Prometheus Radio Project, now Policy Director and Corps supervisor at Prometheus, “In the Belly of the Beast: Washington Insiders & Outsiders Talk Effective Advocacy”

Josh King, served at Active media Foundation, now staff technologist for the Open Technology Initiative at New America Foundation, “Sandbox” Building Community Wireless.”

Cara Lisa Powers, served at United Teen Equality Center, now Co-Director of Press Pass TV, “New Faces of Media Justice”

Kris Rios, served at People’s Production House, now a trainer and the policy program associate at People’s Production House, “Information Exchange Forum for Ethnic Media and Media Advocates”

Wally Bowen, Corps supervisor at Mountain Area Information Network (MAIN), “Closing the Digital Divide: Bringing Down Barriers to Broadband”

Laurie Cirivello, Corps supervisor at Grand Rapids Community Media Center, “Creating and Sustaining Citizen Journalism”

Jessica Collins, Corps supervisor at Media Literacy Project, “Media Literacy for Mobilization: Popular Education Tools for Digital Justice”

Serena Garcia, Corps supervisor at SisterSong, “Media Policy is a Women’s Issue”

Jen Gilomer, Corps supervisor at Bay Area Video Coalition (BAVC), “Open Sourcing Community Media”

Sean McLoughlin, Corps supervisor at Access Humboldt, “Face to Face with the Future of Public Media”

Sascha Meinrath, Corps supervisor at Active Media Foundation, “The National Broadband Plan: A Bold Start or Misssed Opportunity?”

Andrea Quijada, Corps supervisor at Media Literacy Project, “Media Literacy for Mobilization: Popular Education Tools for Digital Justice” and “Mobile Voices, Mobile Justice: A Strategy Session on Telephones, Wireless Policy and Social Change (Part 2)”

Nick Szuberla, Corps supervisor at Thousand Kites, “Mobile Voices, Mobile Justice: A Strategy Session on Telephones, Wireless Policy and Social Change (Part 2)”

Pete Tridish, Corps supervisor at Prometheus Radio Project, Keynote: “Change the Media, Change the World” and “Mr. Radio Goes to Washington: Teaming up to Pass the Local Community Radio Act”

Jack Walsh, Corps supervisor at NAMAC, “Artists and Advocacy: Engaging Creatives to Create Change”

Amplifying impact through the California Council for the Humanities

The Transmission Project is proud to share that two of organizations where we placed Digital Arts Service Corps members this year received grants from the California Council for the Humanities:

The California Council for the Humanities has officially announced its most recent California Story Fund grant award recipients. Twenty projects—selected from among 93 proposals—will collectively receive $199,665 in support through the Council’s California Story Fund. The Fund supports community-centered, story-based public humanities projects that contribute to our evolving understanding of California. In alignment with the Council’s Searching for Democracy initiative, this round of projects examine the meaning of democracy in a variety of ways.

The Khmer Youth Archive Project, $10,000

Sponsoring Organization: Little Tokyo Service Center, Los Angeles

Project Director: Gena Hamamoto

This female youth video project will document the experience of Long Beach Khmer immigrants and refugees. Public screening events and an awareness campaign will involve the community.The Search for Equality: LGBT Stories of Democracy in Action, $10,000

Sponsoring Organization: Media Arts Center San Diego, San Diego

Project Director: Patric Stilman

This film will share stories from San Diego’s LGBT community that explore principles of

democracy, inequality, and activism. Screening events (in partnership with the public library) will facilitate a greater understanding of social and political challenges faced by LGBT people.

The Transmission Project has a long history of working to amplify the impact of other foundations and initiatives in the field such as ZeroDivide, BTOP, and NAMAC’s Capacity Building Support Grant

Honest Practice: How the Public Sector Can Look at Itself (New article in Resources)

We provide here a detailed summary of the article “Honest Practice: How the Public Sector Can Look at Itself” by Howie Fisher with illustrations and design by Billy Brown. Download the full pdf from attachments.

In this article the Transmission Project contests the convention of collecting “best practices” and offers in its place a narrative approach to assessing nonprofit organizations’ capacity building efforts. The Transmission Project calls this approach Honest Practice.

So-called best practices claim to encapsulate successful organizations’ hard-earned knowledge and experience in the form of simple, ready-to-use solutions. Practices are canonized with little regard for what led to success. Research in the field illustrates that what “best practices” obscure is the hard work it takes to get a practice to function correctly in a new environment. The Transmission Project’s observations as capacity-building practitioner attest to the potential pitfalls of blindly adopting so-called best practices.

Although multiple accounts corroborate the risks associated with “best practices,” they remain popular among organizations – primarily as a way to appeal to funders in terms they can grasp. The diversity of nonprofit sector work complicates attempts to establish reliable ways of measuring success while making meaningful comparisons across the field. With the endorsement of funders, “best practices” become a way to discriminate superficially between organizations that do good work and organizations that don’t work.

We explore the depth of the problem. When organizations chase so-called best practices, they under-invest in other forms of overhead. These include evaluation and tracking systems that, when neglected, leave organizations unable to define and measure success on their own terms. The cyclical nature of the problem makes it difficult to address head-on. Without proper infrastructure to measure and understand their work, organizations lose track of their needs and cannot challenge the prescribed standards of excellence.

The fundamental importance of evaluation having been established, the evaluator or researcher emerges as an influential force in representing organizations’ work to funders and the rest of the field. The author suggests that the real challenge is insisting upon a more narrative, process-centered approach to discussing capacity building work as opposed to a myopic focus on success in terms of end results.

The article offers examples of the kinds of qualitative questions writers and researchers can ask. What follows is an analysis of the Transmission Project’s own attempts to evaluate its work without the full support of its funders to do so.

We conclude that while researchers can influence the field by keeping context intact when discussing organizations’ work, evaluation entails not only collecting information, but also processing and integrating it into an organization’s operations. As opposed to relying on “best practices” as markers of success, funders need to provide organizations with the resources to invest in tracking systems to build their capacity to define success, measure it, and articulate what they need to perform better.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Honest Practice - How the Public Sector Can Look at Itself.pdf | 2.69 MB |

Alliance for Community Media Conference 2011

The Alliance for Community Media provides critical support services for community media centers and for the primarily volunteer staff that keep these electronic outposts of democracy in operation. The Alliance’s activities in providing technical assistance, grassroots organizing and opportunities to share experience promote the broader goals of supporting our nation’s communities and families and promoting effective communication through community use of media.

In Pursuit of New Literacies

The concept of digital citizenship – equal participation in a democratic society through digital media – and the corresponding need for digital and media literacy in communities have attracted increased attention thanks to reports such as the FCC’s National Broadband Plan. In support of these ideals, this and similar documents call for the launch of a national Digital Literacy Corps and for increased capacity building of community-based organizations that deliver digital literacy education.

Through the work of its Digital Arts Service Corps members, the Transmission Project is answering the FCC’s call by building the capacity of organizations that provide digital literacy education. The media literacy and production programs run by these community-based organizations inspire people of all ages and of different racial, cultural, and economic backgrounds to create media that represent their perspectives while addressing issues important to their communities. Even the young participants of these programs are making a difference to their communities’ media landscapes today.

Messages in Motion is a project of the Termite TV collective in Philadelphia that puts the tools and skills of video production into the hands of community members who make short “digital postcards” about issues important to them. The videos participants make are then linked to each other based on common themes. Because participants’ creations are both person- and site-specific, the project contributes to a sense of social topography: people are mutually joined by their interest in common issues facing their communities. Even the very young produce films. Participants’ perspectives are unabashedly personal and biased; they do not speak in the detached language of journalism. But by taking part in a dialogue, even these young people can contribute to a sense of community and the exercise of civic life.

The Other Half of the Plan

Alongside recommendations that will expand the work of community-based organizations, the National Broadband Plan supports partnerships between public and private sectors as the most efficient way to deliver quality digital literacy across populations:

NTIA should consider supporting public-private partnerships of hardware manufacturers, software companies, broadband service providers and digital literacy training partners to improve broadband adoption and utilization by working with federal agencies already serving non-adopting communities. Congress should consider providing additional public funds, or NTIA should use existing funds to support these partnerships…

These partnerships would support the communities hit hardest by poverty. Participants would be eligible to receive discounted technology products, reduced-priced service offerings, basic digital literacy training and ongoing support. In addition, these partnerships would offer customized training, applications and tools.

December 13th, 2010 heralded one of the first of such partnerships. Common Sense Media announced in a press release that it would be partnering with Verizon on a digital literacy campaign. The nonprofit will share its “digital literacy and citizenship” curriculum with the telecommunications giant’s Thinkfinity website, and Verizon’s parentalcontrolcenter.com will host weekly Common Sense Media blogs and video tips.

Given the effectiveness of community-based media initiatives, why would a non-profit organization that, according to its website, believes in the principles of “free and independent media,” “media sanity, not censorship,” and “a diversity of programming and media ownership” choose to ally itself with Verizon, a company that has instituted anti-consumer practices, supported unsound and unreliable net neutrality rules, and launched powerfully misleading ad campaigns? What can we expect to develop out of this partnership?

What Does Common Sense Tell Us?

A quick glance at the curricula that this partnership will promote demonstrates just how divorced Verizon and Common Sense Media’s use of digital literacy concepts is from the actual community work and educational reform that digital literacy and citizenship entail.

Common Sense Media’s curricula comprise tools for parents and educators – not kids – to combat the potential hazards of Internet use among children and adolescents and to provide youth with age-appropriate media experiences. Lessons on how to monitor and control kids’ media experiences and teach them to participate “appropriately” online epitomize the organization’s fearful stance vis-à-vis media. A unit on “Connected Culture” purports to explore “the ethics of participating in and building positive online communities,” but focuses almost exclusively on the threat of cyber bullying. Pervasive fear characterizes the video that introduces the unit as positive online interactions among teenagers are twisted into instances of harassment with the help of music and editing. Given Common Sense’s paranoid perspective on media, the positive and negative aspects of online interaction can hardly receive equal treatment.

Common Sense Media has allowed fear of media misuse to over-determine its understanding of digital literacy. Although questions of online etiquette and safety certainly deserve attention, the nonprofit’s fear-based stance toward Media results in an approach to digital literacy education that is not only anti-media, but also anti-child. Consequently, the measures it recommends remain prescriptive and precautionary, not reparative or transformative: filter what content your child sees, punish kids for violating the rules you establish, teach them to behave properly online. Despite Common Sense Media’s claim that it upholds digital media as a platform for community involvement, participation in community is reduced to being a polite citizen and literacy is reduced to knowing how to follow codes of conduct.

Besides adhering to the guidelines the site prescribes, children have little to no role to play in Common Sense’s vision of online civic life. For instance, the site bemoans the ubiquity of sexual imagery in the media and the insidiousness of advertisements disguised as entertainment targeting youth, but does little to discuss how the media might be changed and what role young people can play in this transformation. According to the organization’s beliefs, restricting children’s access to media and making better-informed decisions about media consumption can transform the media landscape. When the website does celebrate kids’ creativity, it cannot do so without touting the same cautionary reminders. Only if kids follow the rules may their creativity “some day make the world a better place.”

Provided Common Sense Media’s protection- and consumer-based methods, its willingness to partner with Verizon seems only logical. Verizon’s Parent Control Center website sells worried parents tools for tracking children’s online behavior. (The Family Locator, Usage Controls, and Security Suite are available to Verizon customers for an additional $4.99 to $9.99/month). The anxious perspective that CSM conveys can only increase the perceived need for such tools. More importantly, Common Sense Media’s parent-focused, passive approach to media reform aids Verizon’s misappropriation of the concepts of digital literacy and digital citizenship. In practice, these concepts call for teaching kids about the media industry itself, including issues of media ownership, affordability, and other barriers to inclusion in online economies as well as how they can change the structure of the media industry to be more accountable to them. By championing the causes of digital literacy and citizenship without tackling Verizon’s role in maintaining barriers to adoption, the telecomm giant and its public sector partner implicate themselves in a travesty of the concepts. Digital literacy demands more than a 21st century update to the Golden Rule.

Community Media as an Answer, not an Alternative

But is Common Sense Media’s philosophy a legitimate insistence on age-appropriate lessons for kids who are too young to understand media bias and ownership, or does it signal ignorance of the difficult, multifaceted work that underlies teaching media literacy while underestimating what young people can do?

Like Termite’s Messages in Motion, the curricula taught at organizations hosting Digital Arts Service Corps members stand in stark contrast to the lessons of Common Sense Media. Rather than offering prescriptive advice for parents, their youth programs show respect for people’s different identities and ignite the creativity of young people to share their perspectives. Ashley was a participant in MIM’s mobile media production studio. Compare her video about her neighborhood with Common Sense Media’s “Digital Creation” presentation. How can CSM claim to promote civic engagement if its proposed solutions only go so far as curtailing kids’ behavior and changing consumer habits? Messages in Motion, on the other hand, forges a connection between creativity and social justice.

Another example: SacYES is an initiative of the Center for Multicultural Collaboration, which has locations in Fresno and Sacramento, California. Program participants are graduates of CMC’s after-school production courses and are paid to make videos, provide technology trainings, and create social media that assists public sector organizations. SacYES and its Fresno counterpart FresYES demonstrate that young people can both create media relevant to social issues and become leaders in their communities.

The Media Literacy Project’s Digital Justice for Us campaign proves that youth can understand media ownership and bias by relating them to their everyday lives. Inner-city youth from Albuquerque record their conversations with peers from rural areas with poor broadband infrastructure. They deploy media to demonstrate how the social ramifications of any medium influence messages conveyed through it. This self-referential use of media is central to any comprehensive notion of digital literacy.

What This Means for Corporate Partnerships and Digital Literacy

Juxtaposing Common Sense Media’s online lessons with community-based approaches emphasizes the inadequacies of public-private models of digital literacy education. Insofar as digital citizenship connotes the extension of civic life to the digital realm, digital literacy efforts will necessarily include components that address how the same racial, cultural, and economic prejudices that exist offline also impact communication online. Sites like Messages in Motion’s can only serve as forums for community discussion if accessible to all. Digital literacy demands that organizations mobilize their constituencies in pursuit of media justice and universal access to information and communications technologies. The leaders in digital literacy education are doing so through the creative use of digital media itself. Unless Common Sense Media and Verizon can meet the same demands, their lessons are a false promise of digital literacy and citizenship.

As is the case with CSM, organizations that claim to promote increased civic engagement across populations through digital media may not recognize what the different needs of communities are, let alone acknowledge that a variety of approaches is required. Based on Verizon’s choice of partners, it seems big companies will ally themselves with organizations whose curricula only reflect the concerns of the company’s current customers, not the growing diversity of Internet technology adopters. The impotence of this particular partnership to meet the digital literacy needs of communiteis casts doubt on the ability of future partnerships to fulfill the role laid out for them in the National Broadband Plan.

The projects and initiatives mentioned here only scratch the surface of the youth programming undertaken at current and former Digital Arts Service Corps sites, and many organizations provide youth programming besides digital video production training, such as online journalism and radio. For a full list of past and current projects, visit http://transmissionproject.org/projectlist

Digital Arts Service Corps Spotlight

After completing his Journalism degree at the University of Wisconsin, Digital Arts Service Corps member Mike Ewing traveled to East Africa to volunteer and work as a freelancer. During his travels through that region he stopped at a small journalism school in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, to speak to the students about working as a reporter in the U.S. Mike said that in talking with those students he came to appreciate how vital community-journalists are to society, and how valuable the community media organizations that support them are.

While there are a number of independent newspapers in Tanzania, corruption is as much a problem in the press as it is in the police. Despite these issues, the young Tanzanian journalists worked with their school to produce independent investigative pieces, creating and maintaining independent sources of information. Now back in the U.S., Mike believes community media institutions should work with nonprofits and citizens to help them not just contribute to the conversation, but to BE the media. While social media and the Internet give everyone a megaphone, Mike said, community media groups can help citizens “use those powers for good.”

Since August, Mike has been working at CAN TV (Chicago Access Network Television) as a Digital Arts Service Corps VISTA. Working closely with the cable access station’s nonprofit clients, he is showing them how to easily and effectively produce videos for the Web. Ultimately, his project will help CAN TV determine how it can better serve nonprofits in the Digital Era. While he worked as an Americorps VISTA at a different organization the previous year, Mike said he was drawn to his current position by the opportunity to realize the free speech ideals that drew him to journalism in the first place.

“In a nutshell, my position provides me with an opportunity to utilize my professional skills to benefit nonprofits and my community. It’s really a no-brainer,” he said.

We are proud to be supporting community access centers like CAN TV through the placement of a Digital Arts Service Corps member like Mike Ewing. We look forward to following his work in the coming months.

To learn a little bit more about Mike and his work at CAN TV, watch this video he made for an AmeriCorps initiative called VISTA Volunteer Reporters.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| spotlight4.jpg | 722.84 KB |